Let’s play a round of “Yellowstone” multiple choice. Ready? Our question: if one follows “Yellowstone” today — and by follow, we mean not just the show, but also the online discourse — which of these answers best applies to how you feel?

A. You hate yourself.

B. You stare into the abyss.

C. You witness and participate in “A metaphor for what we’re experiencing, how the fault lines in our society are manifesting themselves.”

D. All of the above.

Yes, you’re correct. It’s “D.” And no, the quote in C — given to the The New York Times by author Howard David Ingham — is not actually a description of “Yellowstone,” despite being a fitting summation the series’ influence on pop culture. Rather, it’s intended as a description of folk horror, a sub-genre in which an isolated landscape creates and reinforces a warped, often archaic worldview. “Yellowstone” itself is not a folk horror. It’s a western. However, the distinction between how these two genres operate is important, as are the ways in which their overlapping use of both landscape and morality present unique opportunities.

“Yellowstone” is often categorized a “neo-western.” But as The Atlantic’s Sridhar Pappu points out, “Sheridan subscribes artistically to something that looks like the old cowboy way. If his work has a higher moral plane, it’s one governed by cowboy virtues.” If you’re sick of that particular moral plane, you’re not alone. However, since Season 5’s record-breaking premiere demonstrated that over 12 million viewers aren’t sick of it, it’s safe to say Sheridan’s Duttonverse isn’t going anywhere.

There might, however, be a method to more effectively wield Sheridan’s skill set, simply by shifting to a genre better suited to what the writer-director himself previously invested in. And yes, folk horror is the way.

Movie Taylor Sheridan vs TV Taylor Sheridan

As Sheridan explained to DP/30 in 2016, his creative ambition was to shine a new light on important cultural issues. When asked about the overwhelmingly positive response to “Hell or High Water,” Sheridan said he was surprised, given some of the risks he took, including his choice to have a racist protagonist, and his demonstration of how casual racism led down an even darker hole. By presenting that hero (Jeff Bridges’ Marcus Hamilton) as someone who finds his racism funny, Sheridan was forcing the viewer to contend with their response, whatever that response may be. “It’s not the traditional way of approaching social change through art,” Sheridan added.

The sentiments echoed an earlier interview Sheridan gave to Variety, following the release of “Sicario.” In it, the writer discussed the philosophical and practical questions he wanted the film to ask with regard to drug cartels, law enforcement, terrorism, consumerism, and the violent control of a populace, but maintained that it wasn’t the writer’s job to provide a definitive political answer. In both films, Sheridan’s explorations of real-world conflict, tragedy, violence, and consequence (in particular) are unflinching, unromantic, and unwilling to engage in comforting, nostalgic fantasy.

In other words, before Sheridan became the unofficial brand manager for (a very specific ideal of) “rural America,” his goals as a storyteller — both by his own admission and as demonstrated in his work — stood in almost direct contrast to what fans have latched onto in his Paramount Network behemoth. What exactly they’ve latched onto is a point to which we’ll return, but for now, let’s assume Sheridan’s goals haven’t changed. Because if they haven’t, then he’s working in the wrong genre.

Folk horror asks questions that westerns don’t

Rather than simply encourage our empathy by-proxy, folk horror compels us to reflect in real time, to grapple with perspective, to consider the past and our relationship to it, and to confront our own isolation, as well as our own aptitude for constructing myths and monsters.

Summarizing Adam Scovell’s seminal definition of folk horror, author Dawn Keetley writes for Revenant Journal that, “The pressure of the landscape, and the isolation it enforces for its central characters, leads to their ‘skewed belief systems and morality’, which then impels the conclusion of the plot and the final link in the chain, the ‘happening/summoning’, often a violent event.”

These links in The Folk Horror Chain can appear in a variety of ways, but they must appear in some form in order to be folk horror (and not, say, gothic horror, where one is haunted by the past rather than drawn toward its resurgence). What’s important is that these stories employ “the folk,” an isolated landscape and its psychogeography, and a violent collision between a world turned in on itself, and outside forces. Equally important — and another key distinction between folk horror and traditional westerns — is that said collision doesn’t necessarily promote the decision to regress even when it asks us to sympathize with it. Ari Aster’s “Midsommar,” for instance, doesn’t suggest that the solution to the modern world’s rejection of community, connection, selflessness, and empathy, is to join cults and engage in controlled, ritual murder.

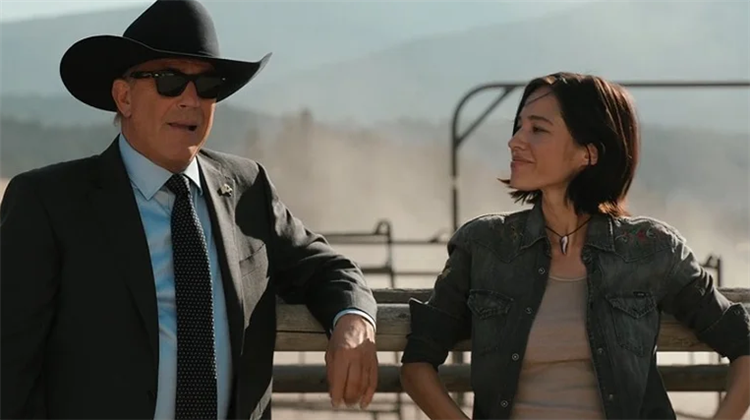

While westerns offer a romanticized version of — as Kevin Costner’s John Dutton would say — “The opposite of progress,” folk horror asks us to think about why societies regress, about the power of both nostalgia and fear, and about the frailty of our own moral superiority.

Taylor Sheridan is half-way to folk horror already

As the aforementioned Ingham writes in “We Don’t Go Back: A Watcher’s Guide to Folk Horror:” “Reason faces off against the old ways, pagan superstitions, old beliefs. We investigate. We divine the rules, discard the old, and make new rules. But we don’t go back […] Except of course if we don’t, it’s an act of hubris. And if we do, it’s madness.”

Landscape, isolation, and skewed morality are already alive and well in Sheridan’s western empire, but the isolation is sought after, and the skewed morality is almost always presented as both sensible and justifiable — even virtuous. Sheridan’s series are also concerned with “the old ways,” but they want, very badly and unambiguously, to go back (or at least stand still) and are inhibited in their investigation of this desire — and of its opposition — by the traditions and moral archetypes of the western genre itself.

“Yellowstone” and its prequels, though they occasionally modernize or invert western tropes, ultimately adhere to a combination of two of the most traditional forms of the genre, as articulated by Professor Patrick N. Allitt in “The Mythology of the American West” – and those are (1) “An apparently ‘bad’ man from the West demonstrates superior moral qualities to those of an apparently ‘good’ one from the East,” as well as (2) “Self-reliant westerners undertake a difficult task and bring it to a successful conclusion.”

Yes, some of the series’ villainous “Easterners” are from California, but the binary of the “Good Rural Outlaw” vs the “Corrupt Coastal Elite” remains. And yet, there’s another way to describe the essential plot of one of the most-watched shows on television.

Surprisingly, Yellowstone is (and isn’t) folk horror

As author Samm Deighan notes in Kier-La Janisse’s “Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror, regarding Tobe Hooper’s “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” – “You get this idea that people are on the land for so long that something happens to the family unit; where there’s this idea of corruption and cruelty; where there’s this sense that family is not a place of love and warmth, but a place where a lot of dark secrets are concealed, and people’s violent natures are given free reign.”

That certainly sounds like “Yellowstone,” as well. And on paper, if not in practice, “Yellowstone” is already folk horror.

The difference between the Duttons and the monstrous Sawyers of Hooper’s gruesome masterpiece is that “Texas Chainsaw” itself doesn’t support the family’s violent response to the outside world, even when it connects that response to their dysfunction and disenfranchisement. This isn’t to say the Duttons have been similarly disenfranchised, but that’s the problem: you’d hardly know it given the enthusiasm with which “Yellowstone” supports its murderous ranch owners. No matter what the Duttons do, whether it’s covering up an execution with another execution, or repeatedly putting a child’s life at risk, we’re meant to be on their side. Every element of the series — from its swelling score, to its purple mountain majesties — is meant to keep us there. Were these actions meant to vilify the Duttons, we’d be talking about a different series entirely.

Nevertheless, the gap between the satirical-sounding plot of “Yellowstone” — a rich, white rancher and his family defend their bajillion acres of land from a local Native American tribe, Californians, eco-activists, a Harvard grad, and a vegan — and the series’ wholly un-satirical tone has been key to keeping itself in the discussion.

Folk horror would allow Sheridan’s work more internal consistency than westerns do

It’s tempting to see “Yellowstone” as an intentional commentary on white, rural anxiety. To be fair, there was a time when “Yellowstone” dabbled in just this sort of complication. That early subversion wasn’t always successful or consistent, but it’s worth considering, since the ratings-motivated devolution of “Yellowstone” — and how it conflicts with Sheridan’s professed artistic goals — speaks to the potential benefits of a more complex, versatile genre.

The fact that Sheridan’s hyperbole has managed to complicate some viewers’ interpretation of the series — e.g., in one Reddit thread, a fan suggests “The showrunners are trying to appeal to the social justice crowd [but…] everyone is cheering for the villains” — doesn’t speak to the series’ subversion of its genre, but to that genre’s limitations. People are cheering for the villains because in-world, the series is telling them to. And the in-world is all that matters in a genre that so wholly rejects the complex reality of our world.

In folk horror, the out-world (aka our world), doesn’t just matter — it’s the key to the narrative’s map. And the genre’s unique ability to speak to more than one experience and identity at the same time makes it an excellent vehicle for social change in fresh, unexpected ways.

For instance, while Sheridan’s big skies and rugged topography reinforce human notions of strength, grit, and perseverance, in folk horror, the landscape’s authority pre-dates the Anthropocene. Sheridan’s landscapes are, in fact, implicated in his characters’ deaths, but his heroes frequently triumph over — and, in the case of “Yellowstone,” even own and successfully manipulate — the land itself.

The Witch, The Wind, and Sheridan

If westerns tells us who does, and doesn’t, “own” the landscape, folk horror reminds us that the landscape has always, and will always, own us. There’s an obsession with the power and apathy of nature in Sheridan’s work — as well as the violent psychogeography of America — that’s already in conversation with both Robert Eggers’ New England folktale, “The Witch,” and Teresa Sutherland and Emma Tammi’s prairie folk horror, “The Wind.”

In “The Witch” and “The Wind,” isolation corrupts and consumes its deluded human inhabitants. In both films, the supernatural does actually occur, but only because we’re seeing it through the lens of an even more inescapable landscape: the mind, or minds, that believe it’s actually occurring. The defense, obviously, is to not believe, but that burden belongs solely to the viewer — it isn’t an in-world option, since these believers don’t see their beliefs as “beliefs,” but as reality. This is another important lesson we can take from folk horror: that acknowledging, investigating, and deconstructing dangerous beliefs is not the same as embracing or excusing those beliefs. On the contrary, it’s a prerequisite for effectively combating them.

The ambivalence with which folk horror views humanity is only half the equation. Folk horror rarely gives its characters the opportunity to escape, and the means by which they fail — (often), either by losing their life or sanity to “the old ways,” or, by becoming a monster in fighting monsters — is an important takeaway. Sometimes (as in “Get Out”) they escape, but sometimes there’s simply no means. Such is the case in Chad Crawford Kinkle’s “Jug Face” — a contemporary Appalachian folk horror in the vein of both Stan Winston’s “Pumpkinhead” and Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.”

Folk horror has no time for false moral equivalence

Of course, all Western folk horror offers a fairly decent parable for the USA (and for the consequences of colonialism in general, and around the globe). The protagonists and victims of “Jug Face,” though — folks whose twisted, horrific mix of fear and faith keeps them tethered to the land, its limited scope, and a supernatural mud pit that requires human sacrifice — offer a specific meditation and commentary without sacrificing nuance, insight, or tension. Not unlike, again, pre-TV Sheridan.

This is similar to the cause-and-effect that we, as viewers, find ourselves wading through during Mia Goth’s nine-minute monologue in “Pearl.” And despite its more picturesque horizons, this is precisely what the Dutton ranch has done to its inhabitants. However, it’s worth noting that Costner’s cowboy King Lear — unlike Pearl’s mother and Ada’s (Lauren Ashley Carter) devout father in “Jug Face” — is not a good person who believes an evil thing. He’s an evil person, portrayed as a good person, who believes in one thing — and that’s himself.

A brief note before we go any further. Though this really should go without saying, allow us to assure you that no, folk horror is not about suggesting that there are “very fine people on both sides” in situations where no moral equivalence exists. In fact, there is never a “both sides” moral equivalence in folk horror, since the structure requires that a rational morality conflict with a skewed and archaic one. Folk horror is, though, about investigating the relationship between isolation, self-narrative, and the past. And as Jordan Peele demonstrates in “Get Out,” these elements needn’t be tied to a rural setting.

The skewed morality of suburbia, as shown by folk horror like Get Out

“Get Out” doesn’t just operate through two worldviews, but through two individual proxies. In the minutes that pass between Chris’ (Daniel Kaluuya) discovery of Rose’s (Allison Williams) photographs and the moment when Rose finally outs herself, the viewer is forced to recognize that, from the outset, Rose has been ignoring and belittling Chris’s concerns, exploiting his vulnerability, and turning him against his own mind. Rose’s “twist” isn’t a twist for everyone, and we must note that Rose doesn’t say, “Sorry, but I can’t give you the keys, babe” — no, she says, “You know I can’t give you the keys, right babe?”

Because of course, he does know. And on some level, he’s known all along. And on some level, so has the Very Good White Liberal Ally who will rage about white, rural anxiety while talking down to Black people (via The Washington Post), viewing empathy as a zero-sum game, and voting to keep their schools and neighborhoods — in some of the country’s most “progressive cities” (via CNN) — segregated. You know I can’t give you the keys, right babe?

These are the levels folk horror operates on. In folklore, metaphors surface unconsciously, as the fears, anxieties, and conflicts of a given people in a given time and place. These manifest in everything from their anecdotes and idioms to their monsters and superstitions. In folk horror, those unconscious manifestations are presented with renewed self-awareness, and used to pull contemporary fears, anxieties, and conflicts — and, most importantly, the tangible consequences thereof — into sharper, more critical focus. By contrast, traditional westerns are more akin to morality plays. They may contain “horror,” but their mythology is presented as reality. Which brings us back to “Yellowstone.”

Yellowstone has become terribly preachy, and the format of westerns is holding Sheridan back

In November 2022, Outkick.com proudly proclaimed that “‘Yellowstone’ Ratings Prove People Love Non-Woke TV.” Well, if “woke” meant prioritizing political correctness and politeness, then said proclamation might work, since no, “Yellowstone” isn’t those things. However, not only is this a fundamental misunderstanding of the term, but the argument itself is demonstrably false, because the aggressive agenda-pushing of “Yellowstone” is everything such critics claim to despise.

Thus far, Season 5 has been nothing but lectures. We’ve heard all about the virtues of small government, the selfishness of the city, the difference between a real feminist and a poser, the value of marriage, and of course, how to be a good wife. We’ve learned about the hypocrisy and greed of environmental activists, and — thanks to the world’s dumbest, most socially inept, most arrogant, and least informed vegan “elite” on the planet, poor Piper Perabo’s Summer Higgins — we’ve even learned some good old fashioned table manners (and how to settle manner-based disputes via properly-supervised fistfights). All of which is to say, yes, some shows do put message-pushing over entertainment, particularly “Yellowstone.”

That the series gave up on its ironic undercurrent as soon as its fanbase pushed back (e.g., Kelsey Asbille’s Monica went, with breakneck speed, from a passionate U.S. history professor to series punching bag, to presumably stay-at-home mom and bona fide preacher of the Dutton gospel) is perhaps not surprising. And if Sheridan’s way of bringing awareness to social issues, as he once claimed was his intent, is to demonstrate just how silly a story can get when its tone, aesthetic, commentary, and arc are written exclusively to appease or enrage factions of the internet … then, g’job, buddy. You really got us. “Yellowstone” has officially brought awareness to … algorithms.

Listen, Yellowstone, with great viewership comes great responsibility

If Sheridan is truly invested in speaking to — and with nuance and realism — what he once described to Esquire as, “The man who’s losing his ranch, who can’t afford his kid’s college — [and who] has no health care,” then using westerns — a genre that not only celebrates, but relies on a lack of nuance and realism — is, to say the least, a limiting choice. And if, as he told the Atlantic, he’s interested in “responsible storytelling” and “real consequences,” then he’s better off putting his affinity for conflicting worldviews, his eye for landscape, and his well-demonstrated passion for psychogeography, to good use in folk horror.

And 12.1 million of us (and counting) would be better off, too. As folklorist Matilda Groves reminds us in her meditation on the genre, “Again, the root word ‘folk’ is key, as it is circumstance that forces the protagonist and we, the readers, into becoming seen as ‘other’ in a world that the protagonist and we, the readers, cannot help but see, ironically, as ‘other.’ The protagonist and we, the readers, are no longer of the common people; we have been forced beyond society and out with the populace. We have become isolated and alone within a crowd.”

We may not all live in — or identity with — the small, rural towns of “Hell or High Water.” But whether we live in a region that’s suffered generation upon generation of extractive industry, generation upon generation of redlining and segregation, or generation upon generation of bigoted legislation and widening gaps in income, health, and education, we all live, to an increasing degree, in isolation. And we are all — save a very small handful of affluent (and actual) elites — “the folk.”