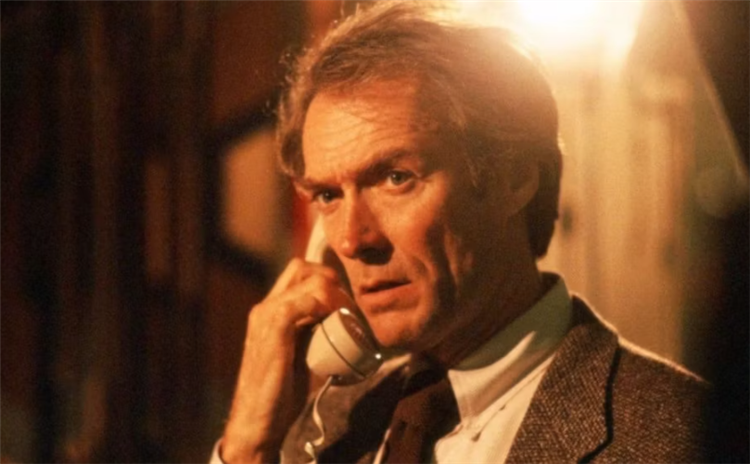

Clint Eastwood has established himself as an effortlessly cool and confident archetype of masculinity, but in 1984’s Tightrope he’s a struggling single father with a complicated relationship with women. The film stars Eastwood as Wes Block, a middle-aged New Orleans police detective attempting to sort out his own sordid desires while solving a series of grisly murders. Unlike his roles in Dirty Harry and the Dollars Trilogy, here is an Eastwood that isn’t breezing through the carnage with ease, but is instead hanging by a thread to provide both emotionally and financially for his two daughters, the oldest of which is played by Eastwood’s real-life daughter Alison Eastwood.

Early on in the film, the dichotomy between Block’s home life and his work as a detective of heinous crimes is put front and center. As Block is preparing to watch a Saints football game with his young daughters Amanda (Alison Eastwood) and Penny (Jenny Beck), he is called into work to take a look at the evidence for the first in the series of murders. The disappointment on the faces of Amanda and Penny is palpable, and Eastwood successfully portrays the sympathetic father who just wants some quality time with his daughters. Instead, he is pulled into the New Orleans dark underworld, and he soon becomes indistinguishable from the kind of people he is investigating.

Usually in films in which a police detective is investigating brothels, strip clubs, and drug dealers, there is a clear line drawn between the keepers of law and order and those trying to disrupt the social order. However, in Tightrope, this dichotomy is immediately proven false as Block receives a sexual favor from the prostitute he interviews following the first murder. Block’s hope resides in his daughters and in the relationship he develops with self-defense instructor Beryl Thibodeaux (Geneviève Bujold) with whom he develops the first normal, healthy relationship he has had in quite a while. Tightrope balances tender human drama with a lurid plot that pushes the boundaries of what is acceptable in a mainstream film.

‘Tightrope’ Is Clint Eastwood’s Grittiest and Sleaziest Film

Tightrope is significantly more downbeat and somber than not only the majority of Clint Eastwood’s own filmography but of many 80s films in general. Tightrope is closer in tone to Taxi Driver or Hardcore than to the many, fluffier cop films of the era. The film is much darker than many of those of the time not only because of its disturbing subject matter but also because of the matter-of-fact manner in which the film’s events are presented. The score is minimal or even completely absent. There are no swanky horns or elaborate arrangements. Oftentimes the only music present is diegetic. The sleazy underbelly of New Orleans is never sensationalized as Block goes on an investigative odyssey into the depths of human depravity.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this section of the film is Block’s struggle with his degenerate desires. This is where the title of the film comes into play, as Block is simultaneously repulsed and titillated by what he sees at night in the French Quarter as he hunts down the killers. In one of the film’s most revealing scenes, Block has a dream in which he is the murderer. The scenes which depict the aftermath of the crimes are shocking in their sheer bluntness. For a film made almost forty years ago, Tightrope’s lurid depiction of New Orleans’ kinky underworld remains as transgressive today as it did in 1984.

‘Tightrope’ Is Part Brian De Palma, Part Paul Schrader

Tightrope owes much of its aesthetic and tone to films like Hardcore and Taxi Driver, as well as the distinctive sleazy sensibilities of many of Brian De Palma’s films at the height of his career, such as Blow Out and Dressed to Kill (both of which came out a few years before Tightrope). Whether it’s the Giallo-style kills that happen offscreen by an unknown assailant, the deep reds and blues which dominate the nighttime color palette, or the vulgar and bizarre wrestling routines at an unconventional strip club straight out of Body Double, Eastwood and Tuggle deliver a unique and disturbing world that dares you to keep watching. The cinematography in these scenes is often darkly-lit juxtaposing those with bright, airy sunlight. The lighting of the former is often uneven and dingy, the latter a collage of vibrant Louisiana tastes and smells.

‘Tightrope’ Examines Masculinity and Fatherhood

Despite the disturbing content in Tightrope, the film is an incredibly empathetic look at masculinity, fatherhood, and failure. At one point when walking through an outdoor market with Beryl, Block mentions that his daughters are the only thing in his life he hasn’t messed up. Block is an incredibly broken man, and the tenderness with which he handles himself among his daughters is not something one would expect from a film this transgressive. Alison Eastwood’s Amanda is a standout in the film, something that can’t be said for many child actors. She gives a very believable and nuanced performance. Her onscreen relationship with her real-life father is natural and unbelievably sweet without veering into schmaltzy melodrama.

In one particularly tender scene, Block has drunk himself to sleep with a picture of his daughters’ mother and ex-wife, a state in which no child should have to see their parent. The poise and maturity with which Amanda helps her father up from his drunken stupor are both lovely and melancholic. In many ways, Amanda is the true heart of the film, as she is old enough to understand what is going on around her, but hasn’t had her innocence obscured by cynicism.

Clint Eastwood Seeks Love In a World of Sex and Violence

Another bright spot in the seedy world of Tightrope is the relationship between Block and Beryl which initially relies on the obvious sexual tension between the two but then develops into something much more wholesome and compassionate. In Beryl, Block sees a lifeline from the empty sexual encounters he partakes in on a regular basis during his nighttime investigative routine. While Beryl is clearly in the story for the sake of Block, she still feels like a person that exists independent of the particular story being told. Geneviève Bujold gives a reserved yet deeply caring performance. Her eyes are deep and warm yet filled with the same fiery intensity that characterizes Block. Bujold is a brilliant and underrated character actor, and her presence helps to lift Tightrope above lesser neo-noir thrillers.

For fans of the genre, Tightrope remains a criminally underseen and underappreciated psychological thriller that doesn’t fall prey to the cheesy tone of many crime dramas in the 80s. The film uses its location to great effect and contains plenty of atmosphere. Tightrope has a solid cast that all provide exceptional performances, a stylishly bleak tone, and just enough humanity to keep it from being nothing more than an exercise in misery. Clint Eastwood may be best known as an impenetrable Western hero, but he is just as compelling as Wes Block — murder, detective, and aging father.