Big cities have become cauldrons of violent crime. Police officers want to help but are hampered by ineffectual policymaking and weak elected superiors. Civilization is on the brink; San Francisco is already over the cliff.

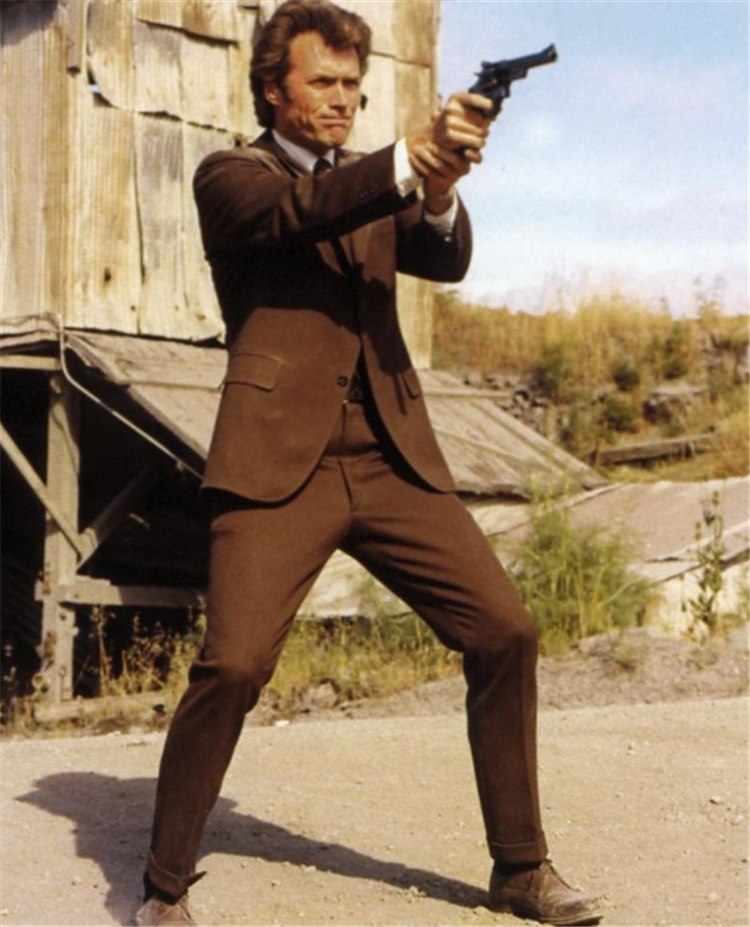

Although these criticisms may seem current today, legendary New Yorker film reviewer Pauline Kael was made aware of them all in January 1972 and refused to engage with them. In that same year, she published a lengthy critique of Dirty Harry by Don Siegel titled “Saint Cop.” Dirty Harry, a smash when it debuted in December 1971, was the first of five movies starring “Dirty Harry” Callahan, a San Francisco police inspector who employs a relentless cruelty in his efforts to restore order to the city’s streets.

It was not a hit with Kael, who, despite being an unusually perceptive observer of the most populist of art forms, once admitted that she lived “in a rather special world” in which she knew just one Nixon voter. Speaking for a loud and vocal minority of non-Nixon voters, then, she objected in the strongest terms politically imaginable, saying that Dirty Harry, which depicts a “Zodiac Killer”-inspired villain as a wanton maniac who is heroically taken down by a dirty police officer, was the fulfillment of the “fascist potential” of the action genre.

“Dirty Harry is not about the actual San Francisco police force,” Kael wrote back then. “It’s about a right-wing fantasy of that police force as a group helplessly emasculated by unrealistic liberals.” Among what the critic considered its many faults, the movie failed to appreciate the nuances of the criminal mind. “Since crime is caused by deprivation, misery, psychopathology, and social injustice,” Kael wrote, rather overconfidently, “Dirty Harry is a deeply immoral movie.”

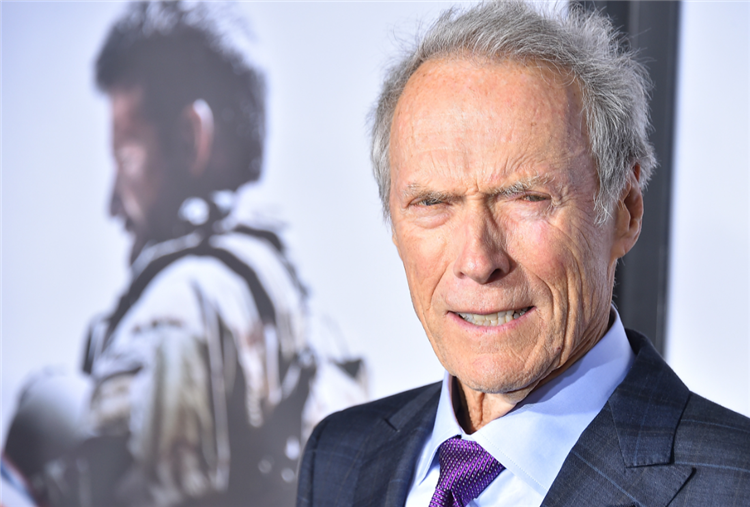

These statements could have been written yesterday, given how the rise in crime now mimics the situation in the 1970s, along with inflation, institutional cynicism, and an ascendant extreme Left. And over the five Dirty Harry movies and his subsequent directorial career as one of the very few conservative Hollywood stars, Clint Eastwood gave America a way to have an honest conversation with itself in fiction about law and order, police violence, and the place of city life itself.

Siegel, a B-filmmaker who had developed a reputation for sleekly efficient genre efforts such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), The Killers (1964), and Madigan (1968), anticipated Kael’s reaction to a story about a police officer who refuses to allow the letter of the law to interfere with his discharge of justice. “I don’t know what people are going to think of this,” Siegel told his friend, the director Peter Bogdanovich. Bogdanovich also wrote that Siegel “thought all his liberal friends would disown him because of the picture’s persuasive portrayal of how difficult it has become for police to apprehend criminals.”

Of course, a hit has a way of soothing anxieties, and Siegel and Eastwood had tapped into what would become a trend. In the wake of the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests, the emergence of the “Manson Family,” and the killing spree of the real-life “Zodiac Killer,” audiences came to take solace in pictures that were attuned to the problem: The Charles Bronson Death Wish series, the vigilantism-goes-rural film Walking Tall, and the feminist-oriented rape revenge drama Lipstick were films that shared Dirty Harry’s approach to law-bending as a means to law enforcement. Kael realized she was on the losing side even at the time of her review. “On the way out, a pink-cheeked little girl was saying ‘That was a good picture’ to her father,” she noted glumly. The Silent Majority went to the movies.

For a time, Eastwood, who, as producer-star, became the prime creative mover behind the sequels, seemed to have developed a degree of defensiveness about his success. The results were often studies in awkwardness: In 1973, Magnum Force required Callahan to serve as an advocate for anti-vigilantism, as the inspector cleaned up a group of Vietnam vets who had come home and joined the SFPD, only to take the law into their own hands, taking the warlike killing way beyond what even old Dirty Harry could countenance. And in 1976, The Enforcer asked Callahan to embrace the presence of a female partner, Kate Moore (Tyne Daly). Vigilantism and misogyny are wrong, but shoehorning such messaging into the Dirty Harry series made for an uneasy fit. Both sequels failed to capture the fundamental appeal of the first film: that, when our neighborhoods are convulsed by chaos, we seek the aid of the police without asking too many questions. The original Dirty Harry fulfilled its function merely by providing an outlet for a fed-up public.

By 1983’s Sudden Impact, the only Eastwood-directed film in the series, everything had returned to the fundamentals. Callahan is alerted to a robbery-in-progress in the rightfully celebrated opening scene when a favorite waitress overdoes the sugar in his coffee. The inspector recognizes the abundance of sweetness as a warning sign and returns to the store to apprehend the offenders. Harry adds, “Smith & Wesson and I. We’re not just going to let you walk out of here.” We clap; the day is complete.

But the emotional core of Sudden Impact is Jennifer Spencer (Sondra Locke), a cool, relentless woman who, seeking “an eye for an eye” in the aftermath of an assault, commences a calculated killing spree. “There is a thing called justice, and was it justice that they should all just walk away?” she asks. Callahan understands her impulse. In a weird but comprehensible sort of logic, his appetite for vengeance is contorted into sensitivity toward victimhood. It might be obvious to people who always disagreed with Kael that there’s nothing contradictory about acknowledging the need for police and hating criminal violence, but it had taken five films for that conversation to play out on screen after San Francisco had gone helter-skelter.

Increasingly, though, the Dirty Harry franchise existed entirely in the realm of popcorn fantasy, which is why the rather sinister implications of his famous catchphrase, “Go ahead — make my day,” were ignored and instead repurposed as a political line by President Ronald Reagan in 1985. The final film in the series, 1988’s The Dead Pool, is well crafted but didn’t have the same real-world reverberations as its predecessors; it wasn’t a vessel for an aging Silent Majority but a mere entertainment. Eastwood, a longtime resident of bucolic Carmel, California, and, for a time in the 1980s, its mayor, became content to let San Francisco sort out its own problems.

With Harry Callahan retired, Clint Eastwood kept at it, engaging with his audience of pre-baby boomer independents, mavericks, and libertarians. 1997’s Absolute Power stars Gene Hackman as a very Clinton-like president whom Eastwood’s character witnesses having sex with the wife of a billionaire political donor. The plot sets off when the affair leads to her murder, and the entire unsubtle script plays like fan fiction for those outraged by the immorality of the Clinton administration, as though it were executive-produced by Juanita Broaddrick. (Extremely anti-Clinton left-wing commentator Christopher Hitchens donated his apartment to the production to use as the set for Eastwood’s character’s hideout.) It’s a strange, fascinating work in which its meditation on the limits of presidential power may now prove uncomfortable for contemporary conservative audiences.

Yet Dirty Harry remains the Clint Eastwood film for the present. Big cities have again become synonymous with lawlessness (including San Francisco itself, though today’s location scouts would no doubt select Portland). Could such a film be made today? Probably not. But, as surely now as in the winter of 1971, such a movie would find a wide and sympathetic audience. Kael felt the first film played on emotion, and higher thinking should prevail. “If you’re intelligent and work this way, you become a cynic; if you’re not very intelligent, you can point with pride to the millions of people buying tickets,” she wrote. But crime only ever waned as a political issue when the actual crime rate waned, not when arguments from theory in the New Yorker won out. People notice their daily reality. Kael failed to ask the basic question that Eastwood answered: Don’t those millions have a point?

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.